From August to October in 2020 and 2021, Dr. H. Bryan Underwood of USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center and Dr. Donald Leopold of SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry studied white-tailed deer in the fertile forests of Delaware. Their goal was to develop a cost-effective and efficient method for estimating deer populations without disrupting park staff. With the help of two graduate students, the researchers explored various existing deer counting methods to estimate the populations in both the First State National Historical Park and the adjacent Brandywine Creek State Park.

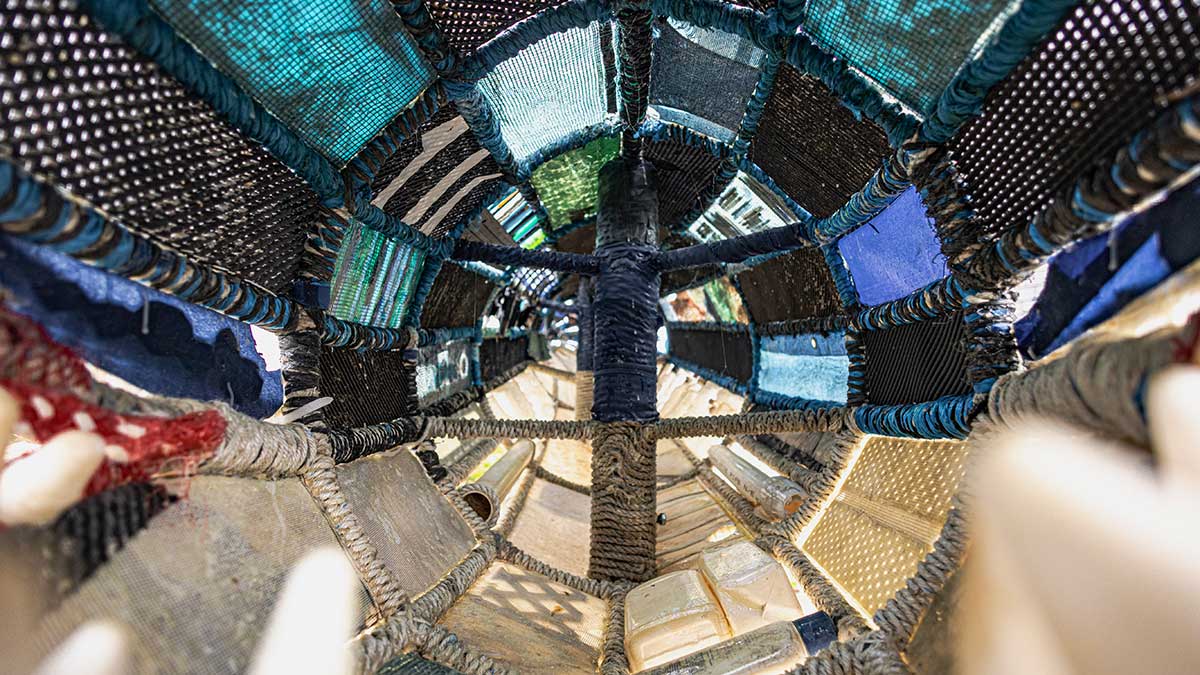

The professors conducted their study using two different field methods simultaneously. One approach involved distance sampling, which required two spotters per vehicle along various accessible roads, while the other utilized a total of sixteen baited and unbaited infrared cameras in areas unreachable by distance sampling. Underwood and Leopold decided that “placing bait, corn weighing just shy about twenty-three kilograms in a V pattern roughly five meters apart from the camera, would be the best way to attract as many deer as possible.” Bait was replenished and resulting data collected weekly, and each year, when October arrived, the cameras were removed from the parks.

One of the professors’ analyses involved sorting images by gender and age group and assigning a species label to create a unique identity for each male based on the number of antler points. These data were used to estimate the deer population with two ratio estimation approaches (Jacobson’s method and Bowden’s estimator). To eliminate overlapping data, the cameras captured loitering deer in bursts of photos separated by three minute intervals in 2020 then extended to five minute intervals in 2021. When questioned about the most noteworthy discovery Underwood stated, the most interesting, but perhaps not surprising, finding was that counts conducted from roads (as opposed to off-road using trail cameras) almost always produced lower estimates of abundance. Underwood also discussed critical facts about climate change and its impact on deer populations in the Northeast. He observed that while harsh winters can reduce deer mortality rates, exposure to novel infections, such as Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease virus (EHD), could significantly increase deer deaths. At smaller protected areas like First State National Historical Park, budget constraints often limit staffing for deer population surveys. The professors aimed to identify an effective and economical method for estimating deer populations without overburdening staff.

Furthermore, projects like this offer valuable research experiences for graduate students, exposing them to real-world challenges and fostering collaboration with agency personnel. Such opportunities help students discover their professional paths. By leveraging their existing skills, they enhanced the research project’s value, transforming a seemingly routine inquiry into something more impactful.

Compiled and written by Shanea Togninalli, NAC CESU Student Assistant at the University of Rhode Island.